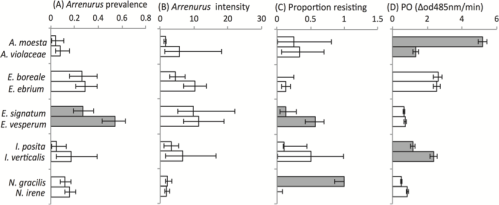

As you know, I have been working on explaining why some damselfly species have more external or internal parasites than other damselfly species (Fig. 1). I was hoping for nice clear patterns, but sadly, as with most study systems of nature that was not meant to be. The story is complicated. It is a very interesting story that I will always find fascinating and hopefully try to resolve in the future, but I needed a change, a new challenge. So I’m moving into a new world, the one of associations between leafminers that feed on asteraceous plants. Even though a lot of research has been done documenting what leafminers feed on what plant, little has been done with this system in the evolutionary ecology context.

Fig. 1 1 A super infected Enallagma ebrium damselfly.

Leafminers are an interesting group because the term does not include one particular family of insects; leafminers can be either flies (agromyzids), micro moths, beetles, or even sawflies. As a group, or guild, they feed on the tissue within leaves but without damaging the upper or lower layers of the leaves (Fig. 2). Some pupate within the leaf, others drop onto the ground and pupate in the ground, it’s a species’ thing.

Fig. 2 A leaf mine on a Solidago gigantea leaf

I have been at collecting leafminers for about a month now. It’s pretty different collecting from the last system I have collected, damselflies and water mites. There are similarities and differences. Here are a few that I noticed so far.

Similarities:

1- Walk around randomly a through a field looking for small things (Fig. 3).

It’d one of the best parts of fieldwork; just walking around fields inspecting every plant for what you are looking to collect. Especially in the type of collecting where you are looking for specific things; as in the case of damselflies and leafminers, you can’t just sweep or pick anything you like, you have to be selective. But that means wandering around looking like you dropped your keys and not caring what anybody thinks about it.

Fig. 3 Walking randomly in the field looking for the specimens you need

2- Challenges of species identification.

It is hard and it takes time to get to know the species you are looking for well enough to be able to find them on the fly. But with enough practice and time, you’ll be able to spot the right habitat for your species straight away and you’ll get a feeling that what you are looking for is there.

3- Overheating because you’re out in the open sun

When collecting in fields, it can get very hot in the middle of the summer. This applies to any collecting if you are not high in elevation or latitude.

4- Sitting in the grass looking at your study and other critters.

The most important part of any fieldwork is sitting down, relaxing and letting the habitat sink in. If there are any type of berries, have a snack! You can be having lunch and observing everything around you. I definitely recommend it for anybody considering themselves field biologists. If somebody considers his/herself a field biologist already knows this though.

Differences:

1- Collecting equipment needed for damselfly collecting – aerial sweep net, vials, notepad, pencil (Fig. 5). Equipment needed for leafminer collecting – vials, notepad, pencil.

Fig. 4 Essentials for damselfly collecting; a net, vials, notebook and something to write with.

Collecting many leafminers doesn’t require any type of specialized equipement other than your fingers. Collecting damselflies with your hands can be done, but if you want to sample many damselflies it would take a long time, I recommend an aerial sweep net.

2- Damselflies fly away, leafminers are stuck in their leaves so they’re not going anywhere.

As most know damselflies are flying insects and they do not want to be caught. They can quickly disappear into the grass or into the trees. It was always quite frustrating, when preparing the sweep net to catch it, it let’s go of it’s perch as is taken by the wind not to be found. I always thought anthropomorphizing “nicely played damselfly, nicely played”. Leafminers on the other hand, because they’re feeding in a leaf, can’t get away. So once you spot one, you can tear of the leaf and the larva will happily keep growing inside as if nothing ever happened. Although the only problem is once the have emerged, you can find empty mines with no leafminer.

3- Challenges of species identification

I know this is in similarities as well, but for damselflies, the challenge it to identify the damselfly to species, and with leafminers, it’s identifying the plant that key. Once the emerge from its pupa, you can identify the leafminer. Although you can make an educated guess about the species based on the mine shape.

5- Collecting damselflies ends at the field, then it’s processing the samples in the lab for parasite determination. You know what you’re getting when collecting damselflies. Since you’ve identified the damselfly while collecting, you know what you have.

Collecting leafminers continues in the lab (Fig. 5); when you’re rearing, you don’t know what is going to be reared from the mine – parasitoids or the actual fly! Which miners have emerged? from what plant? Is it the leafminer or the parasitoid? The anticipation and excitement of finding out what’s going to come out is immense.

Fig. 5 Rearing leafminers from Solidago leaves back in the lab.

Enjoy the outdoors!